Eichmann in Jerusalem

A Report on the Banality of Evil

Hannah Arendt

Global Evaluation: 4.5 out of 5

Global Difficulty: 4 out of 5

Insight: 5 out of 5

Eichmann in Jerusalem was, and to some extent still is, a quite controversial book written by the German-American philosopher Hannah Arendt. Already by the time of its publication, as written in the postscript, the book attracted many criticisms from different sides but that covers mainly Arent’s criticisms of the Jewish religious leaders and the reasons of the trial of the infamous nazi leader Adolf Eichmann. This book, despite its historical importance, must be considered for what it is, i.e., a trial report. The author goes in great detail through the entire trial documenting witnesses, arguments and defense arguments for one of the most famous trials in history where the crime has no precedents and does not appear in any law book. The following article focuses especially in the last two sections of the book, the Epilogue and the Postscript, where the author gives her personal opinion on the entire trial and its outcome.

What follows is mainly inspired (and in some sections is a fairly detailed reproduction of the transcript) of an extremely inspiring resource that I found online. Feel free to check it out if you want.

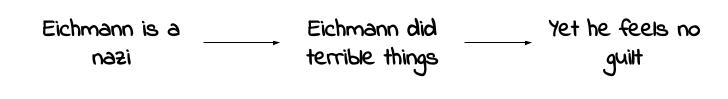

The entire message that Arendt want to give to the reader is a matter of political agency and responsibility; Eichmann was on trial in 1961 for his participation in the holocaust, since he was instrumental to the systematic extermination of millions of jews as well as other persecuted peoples in nazi Germany.

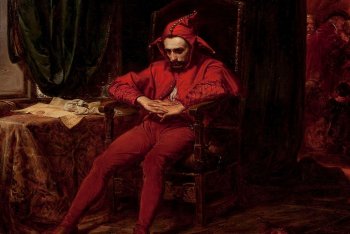

Throughout her work, Arendt consistently arguments against the prosecution’s portrait of Eichmann as some kind of monster or criminal mastermind. Despite all the efforts of the prosecution, everybody could see that this man was not a monster, but it was difficult indeed not to suspect that he was a clown; it’s this characterization of Eichmann as a clown that drew a lot of criticism.

One could argue that in portraying Eichmann as a fool, portraying him as a living joke, Arendt goes too far and there is debate about whether her characterization of Eichmann is accurate or not: one of the crucial things for you to recognize as you’re reading this book is that Arendt is not persuaded that Eichmann is some kind of criminal mastermind.

The question that especially in the last chapter Arentd put forward is: what if Eichmann is not a monster? Eichmann is clearly guilty of committing horrible crimes, but does categorizing him as a monster actually obscure what happened in nazi germany?

Monsters by definition are unusual or atypical creatures and Arendt’s concern is that if we categorize Eichmann and his colleagues as monsters then we might be tempted to understand the horrors of the holocaust as acts perpetrated by a select number of wicked individuals. In the first pages of the work the author explains really well the fact that Eichmann seems an absolutely ordinary person and half a dozen psychiatrists didn’t detect and sign out of the ordinary after interacting with Eichmann.

The entire defense of Eichmann relies indeed on the fact that his only guilt was to be a law abiding citizen and everything he did was simply the implementation of a direct request from one of his superiors. Every other citizen, he argues, would have behaved in exactly the same way if put in his position.

Arendt suggests this is the fundamental key to the whole case, but she says no one in the courtroom really seems notice this point. The problem to her mind was that a normal person neither feeble-minded, nor indoctrinated, nor cynical, could be perfectly incapable of telling right from wrong (like instead seems to be the case of this trial).

So let’s think about this:

So what explains that? was he insane? was he a monster?

Arendt argues that this theory is a red herring, it’s a distraction; if we want to categorize him as as someone abnormal or monstrous, then we have to face the problem that this explanation can’t be used over and over again to account for mass participation in nazi programs. What Arendt draws our attention to is the fact that these extraordinary unprecedented crimes, like the holocaust, can’t be perpetrated by a few evil people that in order for them to happen they require the participation and the support of many many ordinary people. It’s deeply comforting for us to believe that things like nazi Germany happen because there’s some kind of super tyrant like Hitler who forces people to act against their will, against their better judgment, but Arendt argues that’s not the way it works. And so the real philosophical and political theoretical question becomes

“how do ordinary people commit extraordinary crimes?”

or perhaps even more precisely

“what explains widespread participation in totalitarian evil?”

Arendt argues we should not be looking for a psychological profile, but we should instead be looking for the political process that makes unthinkable actions possible. She argues that to blame the holocaust on the moral failures of nazi leaders is just insufficient: we need to focus on the totalitarian regime that makes it possible for large numbers of otherwise normal people to kill millions of innocents. The regime, or political order, matters so much because the question of ordinary people committing extraordinary crimes isn’t just about one person, it’s about many people!

Conventional portraits of unjust regimes focus on the extraordinary appetites of a tyrant or maybe a tyrannical class. Arendt says that what happened in nazi Germany is something profoundly different.

We can trace our understanding of the way that a regime shapes the character of its citizens back to Plato and Aristotle: the basic idea is that different regimes produce different characters (or souls, as the ancients might have said). So while for example a democracy might produce citizens who love freedom, a tyranny produces slaves. Ironically enough also the tyrant itself is a kind of slave, because he himself is controlled by his own appetites (as we see when we look at the works of Plato or Aristotle all the way up through Macchiavelli and Locke). This is the portrait of political injustice that we get and traditionally we think this kind of political evil is motivated by appetites, by greed, by fear, by ambition. But according to Arendt desire and fear do not seem to be the forces driving citizens of totalitarian regimes.

The biggest claim, not only in this book but also in, for example, previous works like “The original of totalitarianisms”, is that nazi Germany is not a tyranny rather it’s a new kind of regime: a totalitarian regime, and to understand totalitarianism we can think about a factory: the totalitarian regime seems to turn people into machines without will, reason, or freedom.

And here we come to the central point of the issue with respect to agency and responsibility. If the totalitarian state reimagines political life as a kind of factory, a series of machines and mechanisms, to what extent do citizens simply become cogs in those machines unthinking automatons? To what extent does the citizen of a totalitarian regime have political agency?

Arendt is occasionally criticized people sometimes read her as suggesting that nazis aren’t responsible for their actions and in saying that Eichmann’s conscience his ability to tell right from wrong does not function in the conventional way, Arendt comes perilously close to saying that we can’t hold Eichmann responsible for his actions. According to the traditional sense of guiltiness, there needs to be in the original action the intention of doing evil. If one person simply doesn’t realize what is he doing, can we really blame him?

BUT that’s not what Arendt believes: this is where the image of the fool becomes extraordinarily important. She claims repeatedly that Eichmann’s problem is a thinking problem! She says for example that he suffers from an almost total inability to look at anything from the other fellow’s point of view; similarly he was genuinely incapable of uttering a single sentence that was not a cliche and that the longer one listened to him the more obvious it became that his inability to speak was closely connected with an inability to think!

Arendt’s claim in this work is going to be that Eichmann’s key problem is that he stopped thinking; he essentially abdicated his rational capacity and sees this as characteristic of citizens living within a totalitarian regime. Totalitarian regimes seem to specialize in preventing rational thought in subverting it and confusing it. From Arendt’s perspective they quite literally become an inhuman regime the moment when a person, a citizen, abdicates the reason and opts not to think. Exactly that is a moment of great moral failure.

In Chapter VIII, Arendt is even surprised when Eichmann summons the Kantian definition of duty and moral precepts. The author says that quite impressively the accused goes really close to the true meaning of Kant’s duty idea, that is, “my will must always be such that it can become the principle of general laws”. What really bothers the author is not that Eichamnn dared to invoke one of the greatest philosophers in history, but the fact that he completely ignored the monumental work that Kant did in the definition of ethical and moral decisions and acts.

Conclusions

So reading Annah Arendt, we are reminded to be vigilant: we need to pay attention to laws, policies, programs, technologies that reduce or limit our agency and our political will; essentially anything that seeks to subvert or diminish our capacity for political decision-making is dangerous.

Acknowledgments

I am profoundly indebted to Prof. Dr. Andrew Moore for his Youtube video and for his work that inspired this entire blog post and review. His clarity and effectiveness has been of great help in writing this work.